Have you ever wondered how to play the violin, the guitar, the flute or the ukulele? The path to mastering these complex skill-sets has a lot in common with every day-to-day task we undertake. There are also many unique angles to fast track you to success.

As a professional musician, I’ve had countless people tell me “I started a musical instrument when I was a kid, but I gave up. I wish I’d kept going.” I see myself as one of the lucky ones who didn’t give up. It’s been 39 years since my first violin lesson and I’ve been fortunate to have made a living as a full-time performer for the past two decades. The unending journey towards an imaginary goal of musical perfection has been rewarding, inspiring and often frustrating. Most importantly I’ve learned a lot. I’ve put together this random hot-pot of some of my discoveries in the hope that it may be of benefit to musicians of all standards and to anyone interested in training the mind.

You may not know exactly how to play the violin after you’ve read this, but it will be some food for thought. And it will probably help you equally well with your piano playing!

[Disclaimer: I have made my best effort, but I apologise in advance for any mis-spellings of the words practice and practise!]

Train and trust the habit mind

Everyone knows that musicians need to practise. Practising is simply a methodical training of the mind. It is a very simple concept.

If you repeat an activity enough times your “habit mind” will eventually learn to do it quite effortlessly. This truth applies to all of us and to all activities. When you are confronted by a section of music which you consider to be “too hard”, “too fast” or whatever, just patiently repeat (and repeat and repeat) it over a period of weeks or months, without too much emphasis on your progress.

Practice and performance are very different

Its essential to immerse yourself in the complex relationship between practice and performance. Your mental picture of how you’d like to perform a piece should inspire and direct your practice sessions. In turn, your practice will allow you to approach the performance you’d like to give. It’s very important that you make a clear mental separation between these two aspects.

Before you play a single note, ask yourself: “Am I practising now, or performing?”.

If you’re practising, be clear on exactly what you are practising, why you are practising it and how you are practising it.

If you’re “performing” (or practising a performance) be clear on exactly how much of the piece you are performing now (eg. the whole piece? Just the first page?) Know why you have chosen to give a performance at this time.

The process of preparing a piece of music for performance is a staggered one. Often I will begin my relationship with a new piece by attempting to “perform” it to get a feel for which bits I immediately find easy and which bits will need to be attacked with formal practice strategies. This initial “performance” is actually just an exploratory exercise.

I would suggest the ratio of time spent on practise vs performance to be at least 10 to 1 or more. One of my teachers used to say “10 times slow, once fast” as a key to this type of mindset.

Be sure to consider any “practise performances” as exploratory exercises only. Do not make them an excuse for self-flagellation! Once you’ve “performed” your segment once and discovered which bits are not currently easy for you – DO NOT PERFORM IT AGAIN until you’ve done a whole lot of practise. Otherwise you risk practising failure, and that’s definitely not how to play the violin!

Don’t practise failure

They say there is no such thing as bad publicity, but there is certainly such a thing as bad practice. Continual repetitions of an inability to play a passage are an aggressive and devastatingly effective form of self-sabotage. Our habit mind is a very powerful but non-discerning tool and will master failure as readily as it masters success.

You should practise any difficult passages separately and repeatedly at a speed at which you can do them. I have found the method of “Accents and Dotted Rhythms” invaluable for practising “fast passages”

Accents and Dotted Rhythms

[This is a very technical bit, probably of little interest to non-musicians]

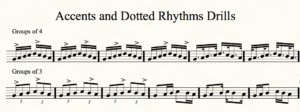

These practice drills are fantastic for several reasons. They force you to play more slowly than you would otherwise and therefore dissuade you from practising failure. They will teach you where your problems actually lie: its amazing how often I’ve thought a problem was in my left hand when it was actually in my right. Also they make a “hard passage” even more difficult than it will be once re-inserted into the musical work. Once you can play the passage perfectly with all these drills it will be a cinch!

Down to details

When you practise a passage where notes are in groups of four (eg. a semi-quaver/sixteenth note run) do this drill:

FIRSTLY: Accent the first of each four, then accent the second of each four, then accent the third of each four, then accent the fourth of each four.

THEN: play the passage with “dotted rhythms” in both combinations – ie long-short then short-long.

Once I’ve perfected this entire drill at a speed which is easy for me I do the whole drill again a little faster.

I have a variation of this drill for passages of notes in groups of three (eg. triplet passages). You can still do the accents (first, second and third note in turn) then, instead of dotted rhythms, play long-short-short, then short-long-short then short-short-long.

See the diagrams at the end of this blog if you find my explanations unclear.

As you practise the drills try not to become frustrated with your imperfections, but be keenly observant and ruthlessly persistent. If a certain note-to-note combination works well with one segment of the drill but not another, this is a fact you can use to devise a plan for improvement. Believe it or not the whole process can be quite fun as long as you avoid misidentifying temporary inabilities as general failures! Playing the violin can become a form of meditation.

Use a metronome

I’m not kidding. Actually use a metronome and actually play exactly in time with it. Be brutal with yourself. Learning to play metronomically will not inhibit your ability to incorporate musical tempo changes into your performance. However, the inability to play metronomically means you are not really in control of what you’re doing.

Weed out impossibilities

Anything which is merely difficult will be achieved with a disciplined practice strategy. However, its important to work out if there are aspects which are simply impossible and how you plan to work around them. For example, there may be two notes on different strings with the requirement for a position change in between which are marked legato. It is physically impossible for these two notes to be perfectly joined, so you need to decide on your work-around. Will you slide or jump? If you slide, which finger will you slide on? Should the slide be audible or will you stop the bow momentarily?

I can’t give advice here on the best technical work-arounds – these must be determined on a case-by-case basis. My point is that technical impossibilities must be identified early in the preparation process. Then they can be accepted rather than seen as a basis for feelings of personal deficiency.

Record yourself

In this era of laptops, phones, pads and pods there is absolutely no excuse for avoiding the thing we all hate the most – recording ourselves. Just do it! And do it often. There is no better teaching and learning tool.

Remember why you’re playing

Music making is an artistic, joyful and even transcendent activity. Many instruments also have added social benefits when you can play them in bands or orchestras. However, if you’re playing the violin just to please another person, pass an exam, prove a point or have a really good-looking bow stroke, maybe it’s time to give up.

Be harsh yet forgiving

You are not your violin playing! There is no point in practising if you don’t aim to improve your skills over the course of time. Therefore you must be always on the look-out for “bad playing”. However, any amount of bad playing does not mean you’re a bad person. So, in short, zealously seek and destroy your musical and technical imperfections, but do not turn the attack cannons on yourself.

Feel free to contact me (Brenton) on info@stringfever.com.au with any comments or questions and sign up for our blogs here

Recent Comments